Dennis Hackethal’s Blog

My blog about philosophy, coding, and anything else that interests me.

Executable Ideas

Talk is cheap. Show me the code.

This article assumes basic knowledge of David Deutsch’s distinction between explicit, inexplicit, and unconscious ideas. If you’re not familiar, read the first ~ten paragraphs of my article on his fun criterion first.

Between explicit, inexplicit, and unconscious ideas, it’s true that one isn’t automatically better than the others. One shouldn’t get to steamroll over the others.

For example, if you have an inexplicit criticism of an explicit idea, then don’t act on the explicit idea anyway just because it’s explicit. Address the criticism first. And vice versa: if you have an explicit criticism of an inexplicit idea, don’t act on the inexplicit idea without addressing the criticism.

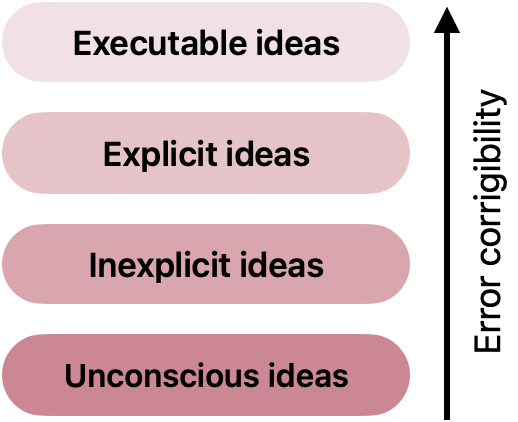

But that doesn’t mean that all three types are all equally conducive to error correction. From that perspective, there is a clear hierarchy.

One benefit of explicit ideas is that they can be brought into direct conflict with each other. You can’t do that with inexplicit or unconscious ideas. Explicit ideas are also usually the easiest to investigate: you can write them down, thereby externalizing them and making them objective. You can pinpoint where they conflict.

Inexplicit ideas aren’t quite as easy to investigate but they still have a crucial advantage over unconscious ideas: at least you’re aware of inexplicit ideas. So you know where to be critical; where to look for errors.

Correcting errors in unconscious knowledge is extremely difficult unless you become aware of it first. That involves gradually de-automatizing knowledge you previously automatized. For example, learning to speak a dialect of your native tongue requires becoming aware of all sorts of things you didn’t even know you did while speaking, eg with your tongue, your jaw, and so on.

Karl Popper said we should create conditions that make it easier to find and correct errors. One way to do this is to translate unconscious into inexplicit and inexplicit into explicit ideas as much as possible. That can be hard, but you should try.

Again, no category of idea is above criticism from the others. And although reasoning and truth-seeking don’t exclusively happen on the explicit level, they’re easier there. If you have an inexplicit criticism of an idea, that criticism still becomes part of the criticism chain. But if you want to be an honest, truth-seeking man, your job is to make a reasonable effort to turn that criticism into an explicit one so the conflict can be resolved more easily.

Making ideas explicit means expressing them in natural language. That requires identifying them. Identification alone can reveal a bunch of errors. But the explicit level can still accommodate a lot of ambiguity, vagueness, and other errors. I believe there is one level above that. This final level is even more conducive to error correction than explicit ideas: executable ideas. Those are ideas we have translated from the explicit level into computer code. They have all the benefits of the explicit level, such as the ability to be brought into direct conflict with each other. An added benefit, however, is that they not only facilitate but demand even more error correction than the explicit level.

For example, it’s one thing to say that addition works by repeat increments. That’s an explicit idea, and it’s true. But it’s quite another to actually write a computer program that adds two numbers and tells you the result. You will go through far more error correction. You have to understand looping or recursion, among other things. Anyone can talk; code is where the rubber meets the road.

Not all ideas make it equally easy to correct errors. The more explicit – or better yet, executable – the easier it usually is.

As any software engineer who has done client work will tell you, to implement a client’s ideas, you need to ask them all kinds of questions. ‘What should happen after a user signs up? Shouldn’t they get a confirmation email? Why couldn’t a user buy the same product twice?’ These questions don’t just help the programmer, they usually help the client understand their own requirements better.

In response to the quote at the beginning of this article, about talk being cheap, somebody wrote:

It's easy for me to outline how a great piece of software X is supposed to function, but I'm still surprised every time how much more work ends up going into the actual implementation compared to the conceptual simplicity of the design. So, similar to "writing is thinking" I believe that "coding is thinking" as well.

In other words, one has to correct far more errors (do “much more work”) to translate an idea from natural language (“conceptual simplicity”) to working code (“the actual implementation”).

In his book The Beginning of Infinity, David Deutsch presents a simple test to judge whether someone has understood some computational task:

[I]f you can’t program it, you haven’t understood it.

If you really want to battle-test an idea (and your understanding of it), code it up. Learning to code has huge epistemological value.

References

This post makes 1 reference to:

There is 1 reference to this post in:

What people are saying