Dennis Hackethal’s Blog

My blog about philosophy, coding, and anything else that interests me.

History of post ‘What Is the Difference Between a Person and a Recording of That Person?’

Versions are sorted from most recent to oldest with the original version at the bottom. Changes are highlighted relative to the next, i.e. older, version underneath. Only changed lines and their surrounding lines are shown, except for the original version, which is shown in full.

Revision 4 · · View this (the most recent) version (v6)

@@ -1,137 +1,137 @@

# What Is the Difference Between a Person and a Recording of That Person?

In "The Beginning of Infinity" (2012, p. 459), David Deutsch asks:

> What is the difference between a computer simulation of a person (which must *be* a person, because of universality) and a recording of that simulation (which cannot be a person)?

Deutsch has discovered that people are computer programs. Running on brains, they are humans, and running on computers other than the brain, [they are are AGIs](/podcasts/artificial-creativity). But either way, they are all people, and since people are programs, they can in principle be recorded --- like all other programs. By that I do not mean surveillance, but something like a video tape.[^1] We do not yet know how to write a computer program that is a person, but no magical essence is required since people must follow the same logic all other programs follow: the step by step execution of code. So I will attempt to answer Deutsch's question by giving examples of simpler programs. I will show how one could go about recording the execution of a program, and then use that to show why a recording of a person cannot *be* a person. I also intend for this to show that knowledge about software engineering can help us attempt to solve philosophical problems.

Consider this simple program:

```clojure

(defn three []

(+ 1 2))

```

This is a *function*. All it does is add 1 plus 2, returning 3. Before we can record this program, we need to run it --- just as before you can videotape something, you need that something to happen: you cannot record a video of a concert without the concert happening in front of you.

We run it like so:

```clojure

(three)

=> 3

```

The double arrow just shows us the function's return value. That's part of what functions do: they optionally take some input (none in the above case), run the steps in the function's body (here `(+ 1 2)`) and then return the result. The body could be much longer and more complicated, but that does not present a problem of principle with recording a program.

A recording of this simple program is just the return value itself. In other words, once we have run the program, we do not need to run it again; we can simply ask "Oh, that function `three`? Yeah it returns the number 3", without having to run it again --- and that's not just because it's named after its return value, but because we have run the function and so we *know* its return value.

The function above is, of course, pretty boring. How about a slightly more interesting example?

```clojure

(defn plus [a b]

(+ a b))

```

This function is different from the previous one in that the numbers it adds up are not always the same. It does not even know what they are. We have to *pass them in* as `a` and `b` whenever we run the function. These are known as a function's *inputs* or *parameters*. For example, we can calculate 2 + 2 by running

```clojure

(plus 2 2)

=> 4

```

We can then record this result and later retrieve its value without running the function again:

```clojure

(look-up plus 2 2)

=> 4

```

Read: "What was the return value of the `plus` function when we ran it with parameters 2 and 2?"

Note, however, that the function's return value may change whenever its parameters change. So after recording this result, we have only recorded one of the infinitely many different additions we could perform. We do know, however, that 2 + 2 is always equal to 4, and so we can confidently store this recording.

This is known as [*memoization*](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memoization) (not memo<em>r</em>ization). It's when you run a function once for some parameters and, next time you run the function with the same parameters, you don't run the function but instead just look up the return value you remember from before.

But that a function can only be memoized for *known* parameters; we cannot look up the result of 3 + 2 if we have not run the function with those parameters yet, just like you cannot remember something that hasn't happened yet. (You can *imagine* it, but that's something different.) Also note that this only works *because* addition always returns the same result for the same inputs.

Now consider this slightly modified version of addition:

```clojure

(defn plus' [a b]

(println "Computing...")

(+ a b))

```

This function (`plus'`, read "plus prime") differs from the previous one in that it prints something to the user before computing and returning the result. In this case, it's a simple message letting whoever is running the function know that it's busy. This would normally be reserved for function calls that take a while, but it illustrates my point: namely, that this function now has a [*side effect*](https://softwareengineering.stackexchange.com/a/40314). The term "side effect" is a bit misleading because it does *not* mean that something is happening that was not intended. A side effect in programming is when a function *changes something somewhere*; for example, printing something to the screen, or writing some value to disk, or mutating some value.

Why do we need to care about side effects? Because we are trying to see if memoization works as a mechanism for recording a function. Let's see what this function does when we invoke it with parameters 5 and 5 for the first time:

```clojure

(plus' 5 5)

; Computing...

=> 10

```

Once we have memoized it, we can look it up:

```clojure

(look-up plus' 5 5)

=> 10

```

So what's the difference? When the look it up, it doesn't print "Computing...". Why not? Because the whole point of memoization is to *not run the function again*, but to instead immediately look up the return value corresponding to the given parameters. After all, memoization is an *optimization* technique. But without side effects, we do not get an accurate recording, and so we would need to come up with a *new* technique that is *like* memoization but *still performs side effects*.

I will get to that shortly, but first I need to mention that we can write functions that do not always return the same value for the same inputs. For example:

```clojure

(defn rand-times [a]

(let [i (rand-int 10)]

(* i a)))

```

First, the function takes a number `a`. Then it generates a random number between 0 and 10 and assigns it to the variable `i`. Lastly, it multiplies `i` by `a` and returns the result.

If you run this function several times with the same input, you will get a different return value almost every time:

```clojure

(rand-times 5)

=> 40

(rand-times 5)

=> 10

(rand-times 5)

=> 25

(rand-times 5)

=> 30

```

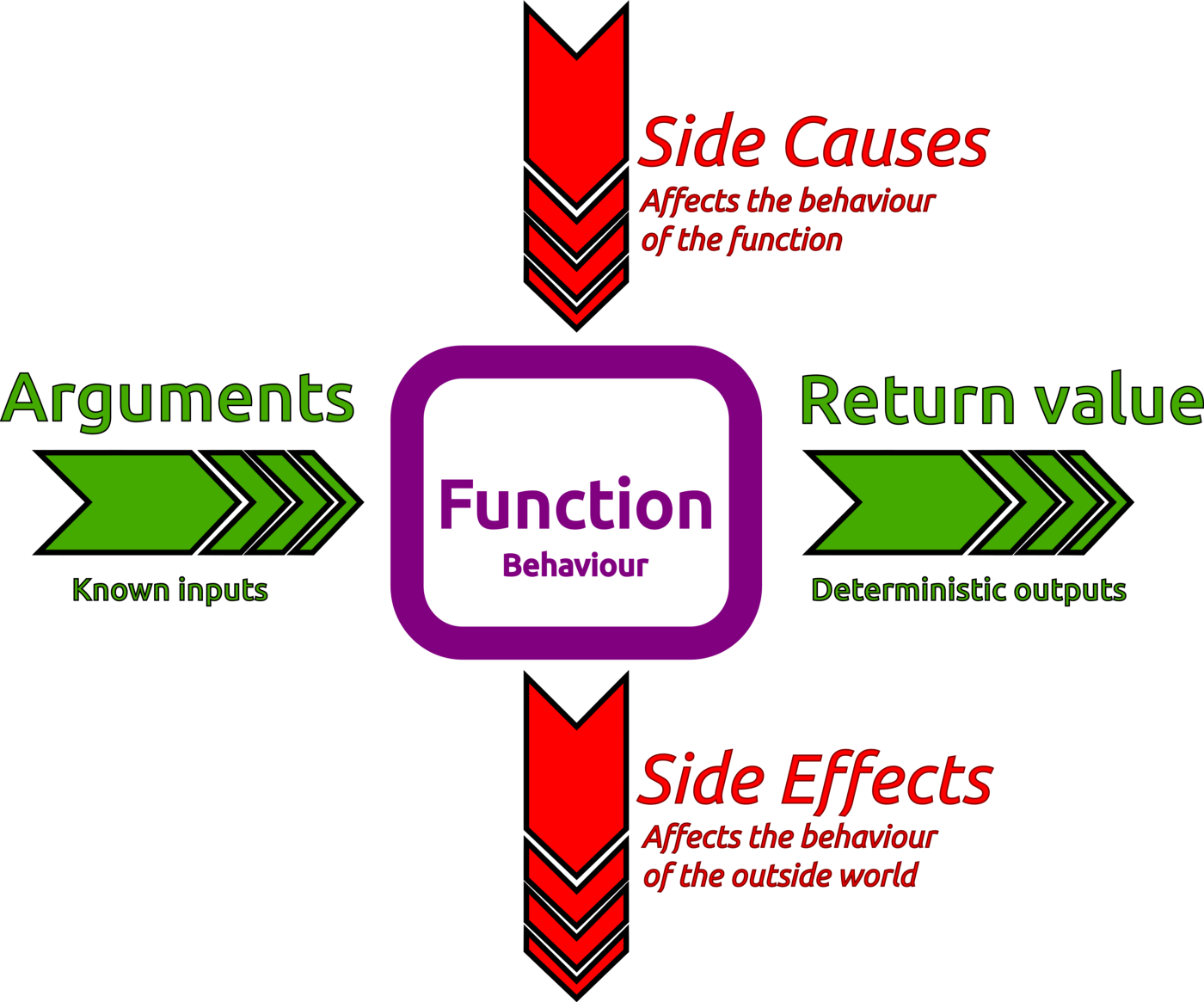

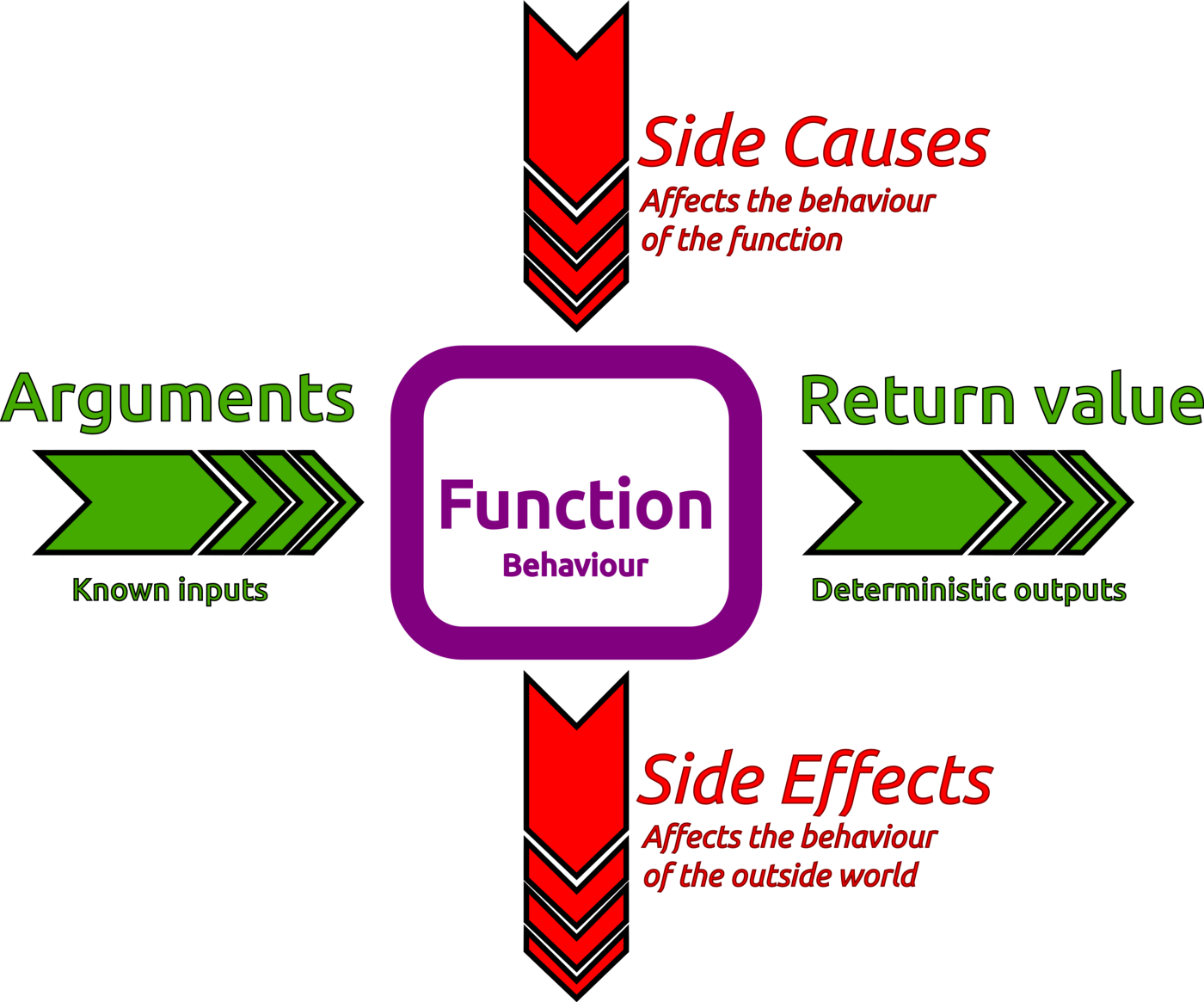

Functions that either do not return the same values for the same inputs, or that have side effects (or both) are known as *impure* functions. Here's an [overview](https://clojurebridgelondon.github.io/workshop/functions/pure-functions.html) from ClojureBridge London.

If any side causes influence a function, or if a function causes any side effects (both red in the picture above), it is impure.

People are impure functions: they have side effects (they shape the world around them, they physically move things, etc), the world around them influences them, and they do not always do the same thing given the same circumstances. A bored person who decides to go to the movies may well, all else being equal, have decided to do something else. (This is because a person is, or at least contains, an evolutionary algorithm he uses to guess solutions to problems, such as what to do when bored, and evolutionary algorithms are always impure. They make people *creative*; creativity is the defining attribute of people.)

Let's extend the above function to also contain side effects. If we can record this impure function, we have found a way to record functions that works:

```clojure

(defn rand-times' [a]

(println "Computing...")

(let [i (rand-int 10)]

(* i a)))

```

It does the same thing as before, with the addition of printing "Computing...". Let's say we invoke function with the number 5, and it happens to generate the number 2 as a random number to multiply by 5. What would a recording of this look like? We know now we cannot use memoization. It would have to be a *new function*:

```clojure

(defn rand-times'-recorded []

(println "Computing...")

10)

```

This is a completely different function. It would have to be the same function to be the same person. And, though it looks a bit like the original, it does something else entirely: it takes *no* parameters and *always* returns 10. The only thing the recording has in common with the original is that it always causes the same side effect. So, if you recorded a person, all their actions would become perfectly reproducible: the opposite of creativity. Since creativity is the defining attribute of people, a function lacking creativity is not a person.

That is the difference between a computer program and a recording of it, and that is why a recording of a person cannot *be* a person.

[^1]: I am ignoring for the moment the moral problem that recording a person violates his privacy. So please, nobody do this once we can program people (i.e. build -AGI).*+AGI).

*If you enjoyed this article, [follow me on Twitter](https://twitter.com/dchackethal) for more content like it.*

Revision 3 · · View this version (v4)

@@ -2,9 +2,9 @@ In "The Beginning of Infinity" (2012, p. 459), David Deutsch asks: > What is the difference between a computer simulation of a person (which-must **be** a+must *be* a person, because of universality) and a recording of that simulation (which cannot be a person)? Deutsch has discovered that people are computer programs. Running on brains, they are humans, and running on computers other than the-brain [they+brain, [they are are AGIs](/podcasts/artificial-creativity). But either way, they are all people, and since people are programs, they can in principle be recorded --- like all other programs. By that I do not mean surveillance, but something like a video-tape*.+tape.[^1] We do not yet know how to write a computer program that is a person, but no magical essence is required since people must follow the same logic all other programs follow: the step by step execution of code. So I will attempt to answer Deutsch's question by giving examples of simpler programs. I will show how one could go about recording the execution of a program, and then use that to show why a recording of a person cannot-*be* a+*be* a person. I also intend for this to show that knowledge about software engineering can help us attempt to solve philosophical problems. Consider this simple program: @@ -13,7 +13,7 @@ Consider this simple program: (+ 1 2)) ``` This is-a *function*.+a *function*. All it does is add 1 plus 2, returning 3. Before we can record this program, we need to run it --- just as before you can videotape something, you need that something to happen: you cannot record a video of a concert without the concert happening in front of you. We run it like so: @@ -22,9 +22,9 @@ We run it like so: => 3 ``` The double arrow just shows us the function's return value. That's part of what functions do: they optionally take some input (none in the above case), run the steps in the function's body-(here `(++(here `(+ 1 2)`) and then return the result. The body could be much longer and more complicated, but that does not present a problem of principle with recording a program. A recording of this simple program is just the return value itself. In other words, once we have run the program, we do not need to run it again; we can simply ask "Oh, that-function `three`?+function `three`? Yeah it returns the number 3", without having to run it again --- and that's not just because it's named after its return value, but because we have run the function and so-we *know* its+we *know* its return value. The function above is, of course, pretty boring. How about a slightly more interesting example? @@ -33,7 +33,7 @@ The function above is, of course, pretty boring. How about a slightly more inter (+ a b)) ``` This function is different from the previous one in that the numbers it adds up are not always the same. It does not even know what they are. We have-to *pass+to *pass them-in* as `a` and `b` whenever+in* as `a` and `b` whenever we run the function. These are known as a-function's *inputs* or *parameters*.+function's *inputs* or *parameters*. For example, we can calculate 2 + 2 by running ```clojure (plus 2 2) @@ -47,13 +47,13 @@ We can then record this result and later retrieve its value without running the => 4 ``` Read: "What was the return value of-the `plus` function+the `plus` function when we ran it with parameters 2 and 2?" Note, however, that the function's return value may change whenever its parameters change. So after recording this result, we have only recorded one of the infinitely many different additions we could perform. We do know, however, that 2 + 2 is always equal to 4, and so we can confidently store this recording. This is known-as [*memoization*](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memoization) (not+as [*memoization*](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memoization) (not memo<em>r</em>ization). It's when you run a function once for some parameters and, next time you run the function with the same parameters, you don't run the function but instead just look up the return value you remember from before. But that a function can only be memoized-for *known* parameters;+for *known* parameters; we cannot look up the result of 3 + 2 if we have not run the function with those parameters yet, just like you cannot remember something that hasn't happened yet. (You-can *imagine* it,+can *imagine* it, but that's something different.) Also note that this only-works *because* addition+works *because* addition always returns the same result for the same inputs. Now consider this slightly modified version of addition: @@ -63,7 +63,7 @@ Now consider this slightly modified version of addition: (+ a b)) ``` This function (`plus'`, read "plus prime") differs from the previous one in that it prints something to the user before computing and returning the result. In this case, it's a simple message letting whoever is running the function know that it's busy. This would normally be reserved for function calls that take a while, but it illustrates my point: namely, that this function now has-a [*side+a [*side effect*](https://softwareengineering.stackexchange.com/a/40314). The term "side effect" is a bit misleading because it-does *not* mean+does *not* mean that something is happening that was not intended. A side effect in programming is when a-function *changes+function *changes something somewhere*; for example, printing something to the screen, or writing some value to disk, or mutating some value. Why do we need to care about side effects? Because we are trying to see if memoization works as a mechanism for recording a function. Let's see what this function does when we invoke it with parameters 5 and 5 for the first time: @@ -80,7 +80,7 @@ Once we have memoized it, we can look it up: => 10 ``` So what's the difference? When the look it up, it doesn't print "Computing...". Why not? Because the whole point of memoization is-to *not+to *not run the function again*, but to instead immediately look up the return value corresponding to the given parameters. After all, memoization is-an *optimization* technique.+an *optimization* technique. But without side effects, we do not get an accurate recording, and so we would need to come up with-a *new* technique+a *new* technique that-is *like* memoization but *still+is *like* memoization but *still performs side effects*. I will get to that shortly, but first I need to mention that we can write functions that do not always return the same value for the same inputs. For example: @@ -90,7 +90,7 @@ I will get to that shortly, but first I need to mention that we can write functi (* i a))) ``` First, the function takes a-number `a`.+number `a`. Then it generates a random number between 0 and 10 and assigns it to the-variable `i`.+variable `i`. Lastly, it-multiplies `i` by `a` and+multiplies `i` by `a` and returns the result. If you run this function several times with the same input, you will get a different return value almost every time: @@ -105,11 +105,11 @@ If you run this function several times with the same input, you will get a diffe => 30 ``` Functions that either do not return the same values for the same inputs, or that have side effects (or both) are known-as *impure* functions.+as *impure* functions. Here's an [overview](https://clojurebridgelondon.github.io/workshop/functions/pure-functions.html) from ClojureBridge London. If any side causes influence a function, or if a function causes any side effects (both red in the picture above), it is impure. People are impure functions: they have side effects (they shape the world around them, they physically move things, etc), the world around them influences them, and they do not always do the same thing given the same circumstances. A bored person who decides to go to the movies may well, all else being equal, have decided to do something else. (This is because a person is, or at least contains, an evolutionary algorithm he uses to guess solutions to problems, such as what to do when bored, and evolutionary algorithms are always impure. They make-people *creative*;+people *creative*; creativity is the defining attribute of people.) Let's extend the above function to also contain side effects. If we can record this impure function, we have found a way to record functions that works: @@ -120,7 +120,7 @@ Let's extend the above function to also contain side effects. If we can record t (* i a))) ``` It does the same thing as before, with the addition of printing "Computing...". Let's say we invoke function with the number 5, and it happens to generate the number 2 as a random number to multiply by 5. What would a recording of this look like? We know now we cannot use memoization. It would have to be-a *new+a *new function*: ```clojure (defn rand-times'-recorded [] @@ -128,10 +128,10 @@ It does the same thing as before, with the addition of printing "Computing...". 10) ``` This is a completely different function. It would have to be the same function to be the same person. And, though it looks a bit like the original, it does something else entirely: it-takes *no* parameters and *always* returns+takes *no* parameters and *always* returns 10. The only thing the recording has in common with the original is that it always causes the same side effect. So, if you recorded a person, all their actions would become perfectly reproducible: the opposite of creativity. Since creativity is the defining attribute of people, a function lacking creativity is not a person. That is the difference between a computer program and a recording of it, and that is why a recording of a person-cannot *be* a+cannot *be* a person.-**I+[^1]: I am ignoring for the moment the moral problem that recording a person violates his privacy. So please, nobody do this once we can program people (i.e. build AGI).* *If you enjoyed this-article, [follow+article, [follow me on-Twitter](https://twitter.com/dchackethal) for+Twitter](https://twitter.com/dchackethal) for more content like it.*

Revision 2 · · View this version (v3)

@@ -105,7 +105,7 @@ If you run this function several times with the same input, you will get a diffe => 30 ``` Functions that either do not return the same values for the same inputs, or that have side effects (or both) are known as *impure* functions. Here's an-overview from [ClojureBridge London's website](https://clojurebridgelondon.github.io/workshop/functions/pure-functions.html).+[overview](https://clojurebridgelondon.github.io/workshop/functions/pure-functions.html) from ClojureBridge London. If any side causes influence a function, or if a function causes any side effects (both red in the picture above), it is impure.

Revision 1 · · View this version (v2)

@@ -1,139 +1,137 @@

# What Is the Difference Between a Person and a Recording of That Person?

In "The Beginning of Infinity" (2012, p. 459), David Deutsch asks:

> What is the difference between a computer simulation of a person (which must **be** a person, because of universality) and a recording of that simulation (which cannot be a person)?

Deutsch has discovered that people are computer programs. Running on brains, they are humans, and running on computers other than the brain [they are are AGIs](/podcasts/artificial-creativity). But either way, they are all people, and since people are programs, they can in principle be recorded --- like all other programs. By that I do not mean surveillance, but something like a video tape*. We do not yet know how to write a computer program that is a person, but no magical essence is required since people must follow the same logic all other programs follow: the step by step execution of code. So I will attempt to answer Deutsch's question by giving examples of simpler programs. I will show how one could go about recording the execution of a program, and then use that to show why a recording of a person cannot *be* a person. I also intend for this to show that knowledge about software engineering can help us attempt to solve philosophical problems.

Consider this simple program:

```clojure

(defn three []

(+ 1 2))

```

This is a *function*. All it does is add 1 plus 2, returning 3. Before we can record this program, we need to run it --- just as before you can videotape something, you need that something to happen: you cannot record a video of a concert without the concert happening in front of you.

We run it like so:

```clojure

(three)

=> 3

```

The double arrow just shows us the function's return value. That's part of what functions do: they optionally take some input (none in the above case), run the steps in the function's body (here `(+ 1 2)`) and then return the result. The body could be much longer and more complicated, but that does not present a problem of principle with recording a program.

A recording of this simple program is just the return value itself. In other words, once we have run the program, we do not need to run it again; we can simply ask "Oh, that function `three`? Yeah it returns the number 3", without having to run it again --- and that's not just because it's named after its return value, but because we have run the function and so we *know* its return value.

The function above is, of course, pretty boring. How about a slightly more interesting example?

```clojure

(defn plus [a b]

(+ a b))

```

This function is different from the previous one in that the numbers it adds up are not always the same. It does not even know what they are. We have to *pass them in* as `a` and `b` whenever we run the function. These are known as a function's *inputs* or *parameters*. For example, we can calculate 2 + 2 by running

```clojure

(plus 2 2)

=> 4

```

We can then record this result and later retrieve its value without running the function again:

```clojure

(look-up plus 2 2)

=> 4

```

Read: "What was the return value of the `plus` function when we ran it with parameters 2 and 2?"

Note, however, that the function's return value may change whenever its parameters change. So after recording this result, we have only recorded one of the infinitely many different additions we could perform. We do know, however, that 2 + 2 is always equal to 4, and so we can confidently store this recording.

This is known as [*memoization*](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memoization) (not memo<em>r</em>ization). It's when you run a function once for some parameters and, next time you run the function with the same parameters, you don't run the function but instead just look up the return value you remember from before.

But that a function can only be memoized for *known* parameters; we cannot look up the result of 3 + 2 if we have not run the function with those parameters yet, just like you cannot remember something that hasn't happened yet. (You can *imagine* it, but that's something different.) Also note that this only works *because* addition always returns the same result for the same inputs.

Now consider this slightly modified version of addition:

```clojure

(defn plus' [a b]

(println "Computing...")

(+ a b))

```

This function (`plus'`, read "plus prime") differs from the previous one in that it prints something to the user before computing and returning the result. In this case, it's a simple message letting whoever is running the function know that it's busy. This would normally be reserved for function calls that take a while, but it illustrates my point: namely, that this function now has a [*side effect*](https://softwareengineering.stackexchange.com/a/40314). The term "side effect" is a bit misleading because it does *not* mean that something is happening that was not intended. A side effect in programming is when a function *changes something somewhere*; for example, printing something to the screen, or writing some value to disk, or mutating some value.

Why do we need to care about side effects? Because we are trying to see if memoization works as a mechanism for recording a function. Let's see what this function does when we invoke it with parameters 5 and 5 for the first time:

```clojure

(plus' 5 5)

; Computing...

=> 10

```

Once we have memoized it, we can look it up:

```clojure

(look-up plus' 5 5)

=> 10

```

So what's the difference? When the look it up, it doesn't print "Computing...". Why not? Because the whole point of memoization is to *not run the function again*, but to instead immediately look up the return value corresponding to the given parameters. After all, memoization is an *optimization* technique. But without side effects, we do not get an accurate recording, and so we would need to come up with a *new* technique that is *like* memoization but *still performs side effects*.

I will get to that shortly, but first I need to mention that we can write functions that do not always return the same value for the same inputs. For example:

```clojure

(defn rand-times [a]

(let [i (rand-int 10)]

(* i a)))

```

First, the function takes a number `a`. Then it generates a random number between 0 and 10 and assigns it to the variable `i`. Lastly, it multiplies `i` by `a` and returns the result.

If you run this function several times with the same input, you will get a different return value almost every time:

```clojure

(rand-times 5)

=> 40

(rand-times 5)

=> 10

(rand-times 5)

=> 25

(rand-times 5)

=> 30

```

Functions that either do not return the same values for the same inputs, or that have side effects (or both) are known as *impure* functions. Here's an overview from [ClojureBridge London's -website](https://clojurebridgelondon.github.io/workshop/functions/pure-functions.html):

-

-+website](https://clojurebridgelondon.github.io/workshop/functions/pure-functions.html).

If any side causes influence a function, or if a function causes any side effects (both red in the picture above), it is impure.

People are impure functions: they have side effects (they shape the world around them, they physically move things, etc), the world around them influences them, and they do not always do the same thing given the same circumstances. A bored person who decides to go to the movies may well, all else being equal, have decided to do something else. (This is because a person is, or at least contains, an evolutionary algorithm he uses to guess solutions to problems, such as what to do when bored, and evolutionary algorithms are always impure. They make people *creative*; creativity is the defining attribute of people.)

Let's extend the above function to also contain side effects. If we can record this impure function, we have found a way to record functions that works:

```clojure

(defn rand-times' [a]

(println "Computing...")

(let [i (rand-int 10)]

(* i a)))

```

It does the same thing as before, with the addition of printing "Computing...". Let's say we invoke function with the number 5, and it happens to generate the number 2 as a random number to multiply by 5. What would a recording of this look like? We know now we cannot use memoization. It would have to be a *new function*:

```clojure

(defn rand-times'-recorded []

(println "Computing...")

10)

```

This is a completely different function. It would have to be the same function to be the same person. And, though it looks a bit like the original, it does something else entirely: it takes *no* parameters and *always* returns 10. The only thing the recording has in common with the original is that it always causes the same side effect. So, if you recorded a person, all their actions would become perfectly reproducible: the opposite of creativity. Since creativity is the defining attribute of people, a function lacking creativity is not a person.

That is the difference between a computer program and a recording of it, and that is why a recording of a person cannot *be* a person.

**I am ignoring for the moment the moral problem that recording a person violates his privacy. So please, nobody do this once we can program people (i.e. build AGI).*

*If you enjoyed this article, [follow me on Twitter](https://twitter.com/dchackethal) for more content like it.*

Original · · View this version (v1)

# What Is the Difference Between a Person and a Recording of That Person?

In "The Beginning of Infinity" (2012, p. 459), David Deutsch asks:

> What is the difference between a computer simulation of a person (which must **be** a person, because of universality) and a recording of that simulation (which cannot be a person)?

Deutsch has discovered that people are computer programs. Running on brains, they are humans, and running on computers other than the brain [they are are AGIs](/podcasts/artificial-creativity). But either way, they are all people, and since people are programs, they can in principle be recorded --- like all other programs. By that I do not mean surveillance, but something like a video tape*. We do not yet know how to write a computer program that is a person, but no magical essence is required since people must follow the same logic all other programs follow: the step by step execution of code. So I will attempt to answer Deutsch's question by giving examples of simpler programs. I will show how one could go about recording the execution of a program, and then use that to show why a recording of a person cannot *be* a person. I also intend for this to show that knowledge about software engineering can help us attempt to solve philosophical problems.

Consider this simple program:

```clojure

(defn three []

(+ 1 2))

```

This is a *function*. All it does is add 1 plus 2, returning 3. Before we can record this program, we need to run it --- just as before you can videotape something, you need that something to happen: you cannot record a video of a concert without the concert happening in front of you.

We run it like so:

```clojure

(three)

=> 3

```

The double arrow just shows us the function's return value. That's part of what functions do: they optionally take some input (none in the above case), run the steps in the function's body (here `(+ 1 2)`) and then return the result. The body could be much longer and more complicated, but that does not present a problem of principle with recording a program.

A recording of this simple program is just the return value itself. In other words, once we have run the program, we do not need to run it again; we can simply ask "Oh, that function `three`? Yeah it returns the number 3", without having to run it again --- and that's not just because it's named after its return value, but because we have run the function and so we *know* its return value.

The function above is, of course, pretty boring. How about a slightly more interesting example?

```clojure

(defn plus [a b]

(+ a b))

```

This function is different from the previous one in that the numbers it adds up are not always the same. It does not even know what they are. We have to *pass them in* as `a` and `b` whenever we run the function. These are known as a function's *inputs* or *parameters*. For example, we can calculate 2 + 2 by running

```clojure

(plus 2 2)

=> 4

```

We can then record this result and later retrieve its value without running the function again:

```clojure

(look-up plus 2 2)

=> 4

```

Read: "What was the return value of the `plus` function when we ran it with parameters 2 and 2?"

Note, however, that the function's return value may change whenever its parameters change. So after recording this result, we have only recorded one of the infinitely many different additions we could perform. We do know, however, that 2 + 2 is always equal to 4, and so we can confidently store this recording.

This is known as [*memoization*](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memoization) (not memo<em>r</em>ization). It's when you run a function once for some parameters and, next time you run the function with the same parameters, you don't run the function but instead just look up the return value you remember from before.

But that a function can only be memoized for *known* parameters; we cannot look up the result of 3 + 2 if we have not run the function with those parameters yet, just like you cannot remember something that hasn't happened yet. (You can *imagine* it, but that's something different.) Also note that this only works *because* addition always returns the same result for the same inputs.

Now consider this slightly modified version of addition:

```clojure

(defn plus' [a b]

(println "Computing...")

(+ a b))

```

This function (`plus'`, read "plus prime") differs from the previous one in that it prints something to the user before computing and returning the result. In this case, it's a simple message letting whoever is running the function know that it's busy. This would normally be reserved for function calls that take a while, but it illustrates my point: namely, that this function now has a [*side effect*](https://softwareengineering.stackexchange.com/a/40314). The term "side effect" is a bit misleading because it does *not* mean that something is happening that was not intended. A side effect in programming is when a function *changes something somewhere*; for example, printing something to the screen, or writing some value to disk, or mutating some value.

Why do we need to care about side effects? Because we are trying to see if memoization works as a mechanism for recording a function. Let's see what this function does when we invoke it with parameters 5 and 5 for the first time:

```clojure

(plus' 5 5)

; Computing...

=> 10

```

Once we have memoized it, we can look it up:

```clojure

(look-up plus' 5 5)

=> 10

```

So what's the difference? When the look it up, it doesn't print "Computing...". Why not? Because the whole point of memoization is to *not run the function again*, but to instead immediately look up the return value corresponding to the given parameters. After all, memoization is an *optimization* technique. But without side effects, we do not get an accurate recording, and so we would need to come up with a *new* technique that is *like* memoization but *still performs side effects*.

I will get to that shortly, but first I need to mention that we can write functions that do not always return the same value for the same inputs. For example:

```clojure

(defn rand-times [a]

(let [i (rand-int 10)]

(* i a)))

```

First, the function takes a number `a`. Then it generates a random number between 0 and 10 and assigns it to the variable `i`. Lastly, it multiplies `i` by `a` and returns the result.

If you run this function several times with the same input, you will get a different return value almost every time:

```clojure

(rand-times 5)

=> 40

(rand-times 5)

=> 10

(rand-times 5)

=> 25

(rand-times 5)

=> 30

```

Functions that either do not return the same values for the same inputs, or that have side effects (or both) are known as *impure* functions. Here's an overview from [ClojureBridge London's website](https://clojurebridgelondon.github.io/workshop/functions/pure-functions.html):

If any side causes influence a function, or if a function causes any side effects (both red in the picture above), it is impure.

People are impure functions: they have side effects (they shape the world around them, they physically move things, etc), the world around them influences them, and they do not always do the same thing given the same circumstances. A bored person who decides to go to the movies may well, all else being equal, have decided to do something else. (This is because a person is, or at least contains, an evolutionary algorithm he uses to guess solutions to problems, such as what to do when bored, and evolutionary algorithms are always impure. They make people *creative*; creativity is the defining attribute of people.)

Let's extend the above function to also contain side effects. If we can record this impure function, we have found a way to record functions that works:

```clojure

(defn rand-times' [a]

(println "Computing...")

(let [i (rand-int 10)]

(* i a)))

```

It does the same thing as before, with the addition of printing "Computing...". Let's say we invoke function with the number 5, and it happens to generate the number 2 as a random number to multiply by 5. What would a recording of this look like? We know now we cannot use memoization. It would have to be a *new function*:

```clojure

(defn rand-times'-recorded []

(println "Computing...")

10)

```

This is a completely different function. It would have to be the same function to be the same person. And, though it looks a bit like the original, it does something else entirely: it takes *no* parameters and *always* returns 10. The only thing the recording has in common with the original is that it always causes the same side effect. So, if you recorded a person, all their actions would become perfectly reproducible: the opposite of creativity. Since creativity is the defining attribute of people, a function lacking creativity is not a person.

That is the difference between a computer program and a recording of it, and that is why a recording of a person cannot *be* a person.

**I am ignoring for the moment the moral problem that recording a person violates his privacy. So please, nobody do this once we can program people (i.e. build AGI).*

*If you enjoyed this article, [follow me on Twitter](https://twitter.com/dchackethal) for more content like it.*